“He was not very tall, but very stocky and strong, with a cold and terrible appearance, a strong and aquiline nose, swollen nostrils, a thin reddish face in which very long eyelashes framed large wide-open green eyes; the bushy black eyebrows made them appear threatening. His face and chin were shaven, but for a mustache. The swollen temples increased the bulk of his head. A bull's neck connected his head to his body from which black curly locks hung on his wide-shouldered person.”

— Niccolò Modrussa, Florentine at the court of the Hungarians who met and described Vlad in his writings

INTRODUCTION: TRANSYLVANIAN HORROR

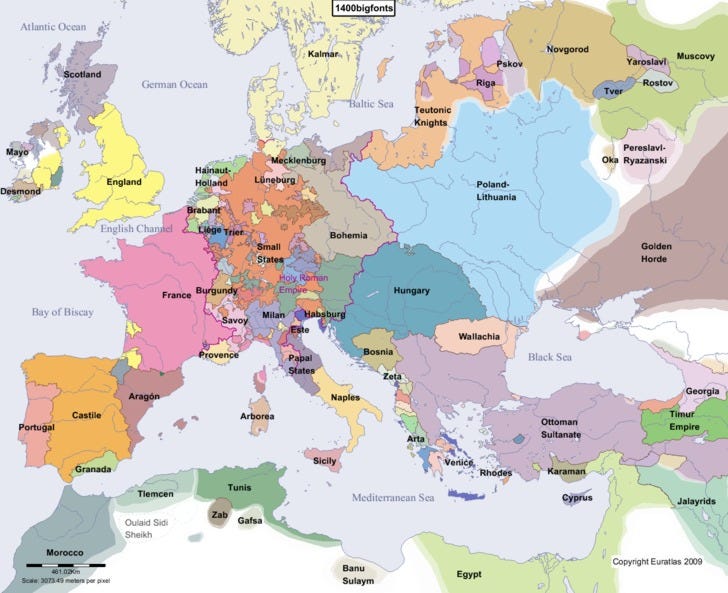

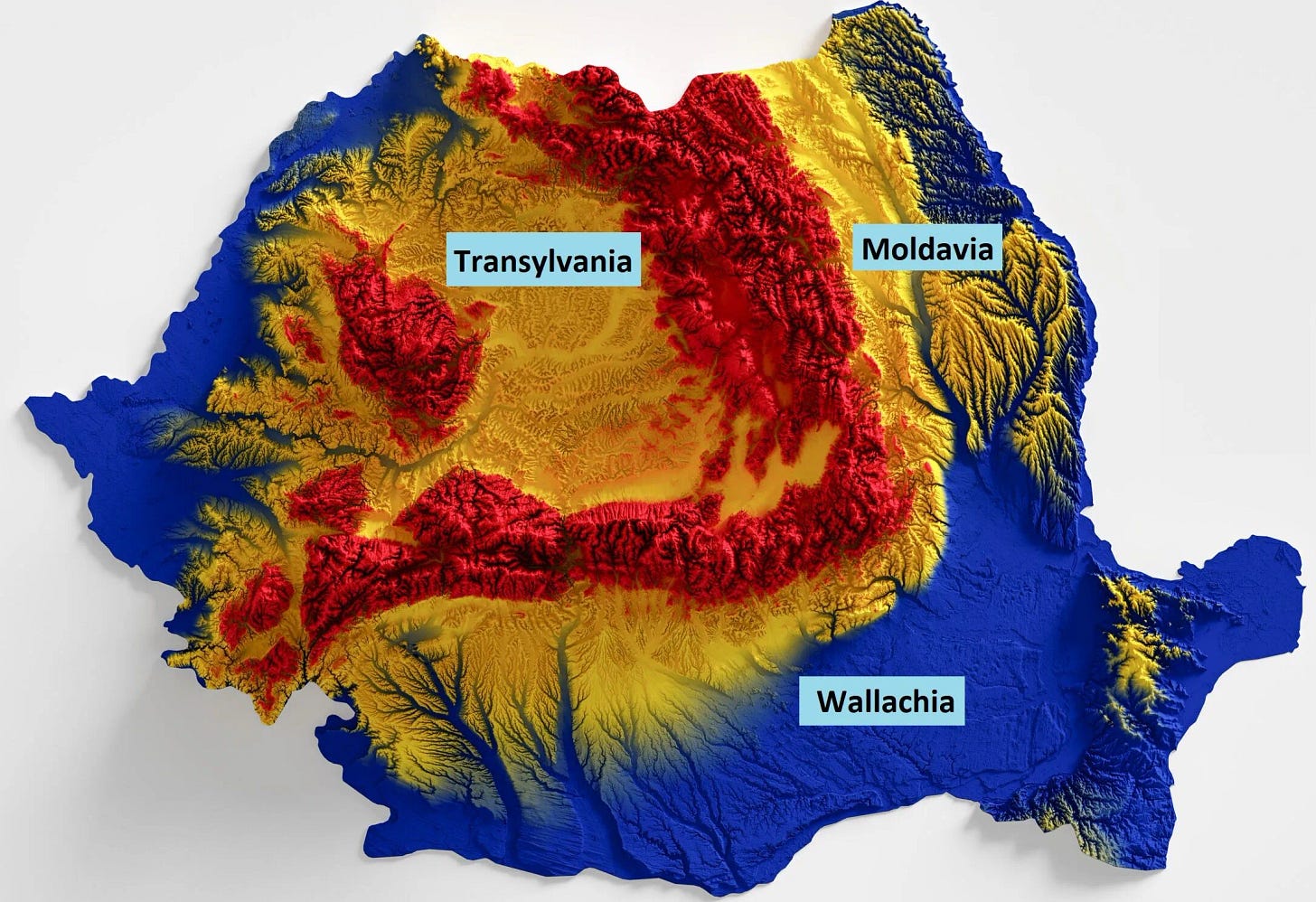

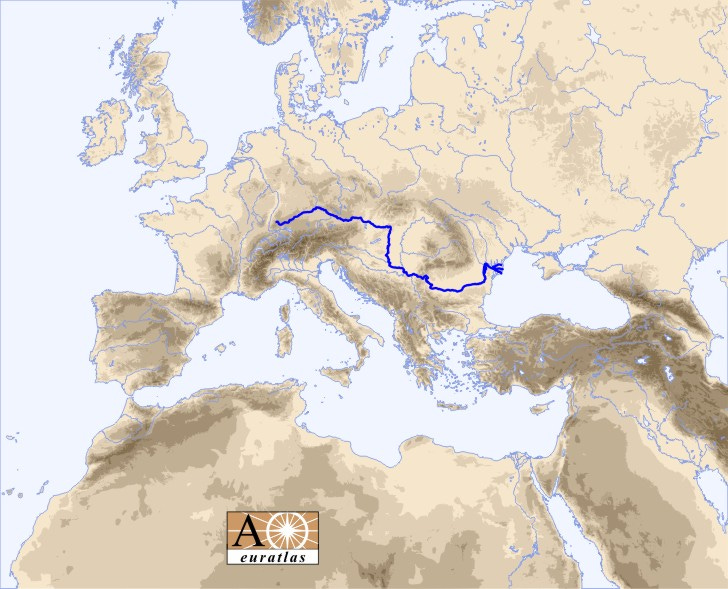

In 1459, Transylvania was the Southeastern most region of the Hungarian Empire and, in turn, the Southeastern most edge of Western Christendom. The Carpathian mountains formed the southern border, splayed across the hazy horizon in rolling forested hills that dramatically increased in severity as they marched east, culminating in the Fagaras range, consisting of more than a dozen rocky peaks over 8,000 feet high. Beyond the mountains to the south lay foreign lands occupied by heathen Turks against whom the European Christians had finally ceased crusading after their recent, crushing defeat at Varna in 1444. But across the Transylvanian border, between the southern slopes of the Carpathians and the farthest eastern expanse of the Danube river, resided the kingdom of Wallachia, the last independent European region south of Hungary after the Ottomans conquered Serbia in 1389, Bulgaria in 1396, and Constantinople in 1453. Wallachia was not a Catholic nation, but an isolated Eastern Orthodox country, caught in its final death throes between two superior forces of disparate religions and imperial interests that hardly took account of its sovereignty. From this tiny, doomed region arose one of the most daring, uncompromising, and fierce warlords of the Middle Ages, who went on to become one of the most feared names in world history: Vlad III, Dracula.

The Fagaras

The Piatra Craiulu range, just east of the Fagaras and south of Brasov

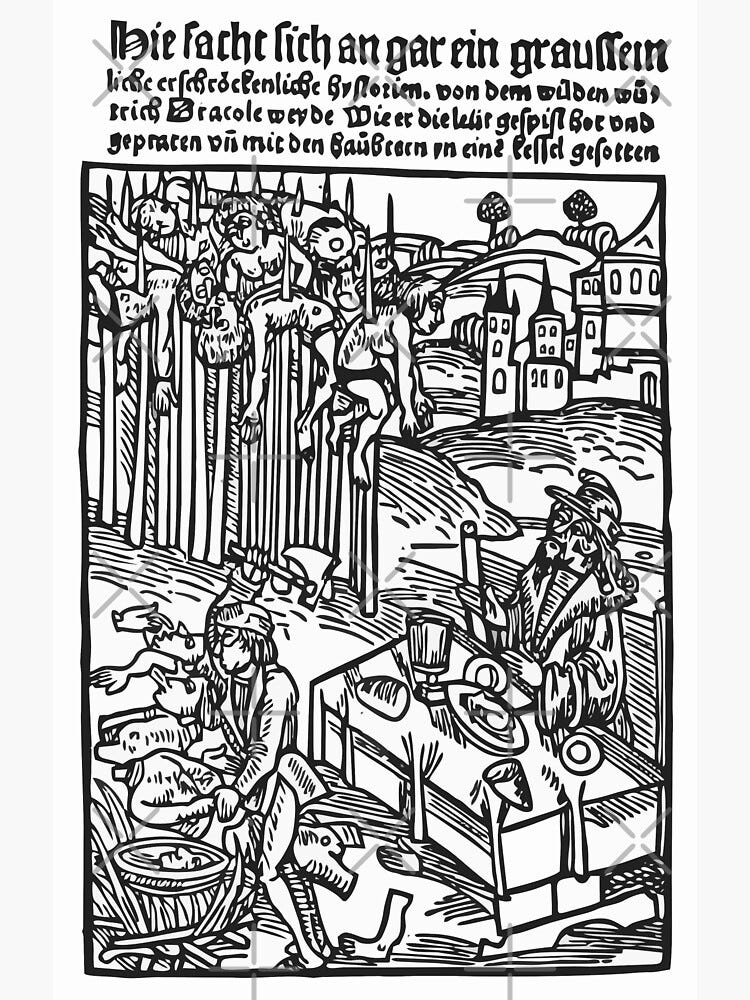

In the summer and early autumn of 1459 Vlad Dracula, with a contingent of fiercely loyal, newly appointed men-at-arms, rode over the Carpathian passes and down their northern slopes into Transylvania to spread horror, torture, and mass execution across several settlements in the shadow of the Fagaras. It was this reign of terror, which did not end until the next year, that gave birth to the legend we know today as Count Dracula. As the summer sun gave way to cool autumn breezes coming down off the mountains, Vlad and his men committed dozens of atrocities that were immortalized in German pamphlets and chronicles, widely disseminated throughout Europe to people who’d probably never heard of Transylvania, let alone Wallachia. These pamphlets and chronicles, replete with now-famous wood carvings, began to appear roughly a decade after Vlad’s death, though reports of his abuses appeared immediately.

The stories about Vlad here are scintillating in their brutality and broad in scope, taking place across most of Southern Transylvania, but this was only one instance of the terror he rained down on his enemies and those who betrayed him and his family. The survivors and witnesses to the scourging of Transylvania reported that he

…invaded Tara Barsei and spoiled the rye and ruined all the corn in the fields…and the people were all captured outside of Brasov. Dracula went into Brasov as far as the chapel of St. Jakob and ordered that the suburbs of the city should be burned down. And no sooner had he arrived there, when early in the morning he gave orders that the men and women, young and old alike, should be impaled next to the chapel, at the foot of the mountain. He then sat down at a table in their midst and ate his breakfast with great pleasure…

…he had people shredded like cabbage and took others away to his country where he had them impaled…

…in the year 1460, on St. Bartholomew’s Day, in the morning, Dracula crossed the forest with his servants and looked for all the Saxons, of both sexes, around the village of Amlas, and all those that he could gather together he ordered to be thrown, one on top of the other, like a hill, and to slaughter them like cabbage, with swords and knives…

…and then he had a big copper cauldron built and put a lid made of wood with holes in it on top. He put the people in the cauldron and put their heads in the holes and fastened them there; then he filled it with water and set a fire under it and let the people cry their eyes out until they were boiled to death…

…and then, from all the lands which are called Fagaras, he took the people and brought them to Wallachia, men, women, and children, and he ordered that all of them be impaled…

These are only a few anecdotes among dozens detailing his actions in Transylvania, where he burned down churches, impaled priests, destroyed crops, and took hundreds, if not thousands of prisoners back to Wallachia and had them added to his infamous forest of the impaled. By 1500 the pamphlets had been circulating for decades, and as they did more and more stories were added. At this point, 25 years had gone by since his death and 4 decades had passed since the events in question transpired, and historians suspect that several stories were either heavily embellished or made up entirely.

Among some of these exaggerations were that he had 30,000 people killed in Amlas, and that he rounded up 300 male children living in Wallachia whose parents had fled to Brasov, and had them impaled or burned to death. The exaggerations, however, were not of the killings themselves, but of the number of people killed. For example, the number of boys killed in Wallachia was probably closer to 200, and Amlas couldn’t possibly have even had 30,000 residents in total. The stories purported to be made up involve boiling or roasting people alive and forcing their countrymen to eat them before they themselves were executed, decapitated men whose heads were used to fertilize Vlad’s cabbage-patch, stories of men being forced to eat the breasts of their wives after they’d been cut off, while their wives were being impaled alive, and convoluted stories of tricks and deceptions he played on Transylvanian merchants while they sold their wares inside Wallachia. No evidence beyond the time-lapse and the impossible knowledge of details adds credibility to the claims of invention, however we can be sure the stories were based in truths that became distorted with time and retelling.

While Vlad’s entire life as a free man and Voivode -the Romanian word for warlord - is rife with both brutal violence and riveting battles, it was these Transylvanian stories that earned him a reputation in Europe, and grew into the vampire stories we know today. None of these stories have him keeping women as thralls or drinking people’s blood, though several exist of him eating among the dying impaled and dipping his bread in their blood. Still, some vague shadows of reality and the legends that sprang up can be found in the pages of Bram Stokers novel, such as babies being ripped from their mothers, an imprisoned man subjecting insects and rodents to torture, confiscated treasure, grim burials and exhumations, and distant memories of great battles fought by a once noble line of Romanian kings and princes. These Transylvanian stories, however, were only the reports that made it into Europe. These acts, or at least these types of acts, were corroborated by chroniclers, letters, and historians from Moldavia, Hungary, Wallachia, Byzantium, Turkey, and even Vlad himself.

What we see when studying the history of Vlad the Impaler is that the assault on Transylvania in 1459-60 was not the first, nor the last, acts of mass murder, pillaging, raiding, or warfare he committed. In fact, these acts and more define his entire life, a life that resembles more the fictional character of Conan the Barbarian from the John Milius film than Count Dracula from Bram Stokers novel. Nor do we find these were the singularly depraved, inhuman acts of a bloodthirsty, evil villain, but rather the shrewd, cunning, and in many cases stunningly brave acts of a man beset quite literally on all sides by hostile forces who were much more powerful than him. Not only that, much of the punishment he dealt out to his enemies was par for the course in one of the most brutal, murderous, and war ravaged time periods in European history, in one of the most unstable regions in Europe from the time of the fall of Rome until even today.

HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, AND LEGEND

We’ve already seen Vlad ravage southern Transylvania, specifically the villages and towns of Amlas, Fagaras, and Tara Barsei and Brasov, and to these we will add Sibiu, which is in the same region and plays a role similar to the others, as we shall see. These stories did not find their way back to the Europe simply because this region was part of the Hungarian Empire, but because it was heavily populated by Germans from the low-countries and Saxony. In fact, while the peasant class was Romanian, and many of these regions were very recently provinces of Wallachia, Saxon emigrants had been settling there for hundreds of years at the invite and with the help of Romanian nobles, known as Boyars, and various Europeans, such as the Knights Templar. These inhabitants were known as Transylvanian Saxons, and they had been coming to Transylvania since the 12th century to set up trade and establish a money economy in a region that was geographically isolated and economically agrarian. These Transylvanian Saxons, along with their Romanian Boyar allies, were the objects of Vlads assault, and it was they whom he tortured and had shipped to Wallachia for impalement. Furthermore, Amlas and Faragas were regions his family once lorded over that had recently aligned with the Transylvanian Saxons, who refused to return their lands to Wallachia.

(map of Europe in 1400).

(map of Romania. Tara Baresi is a region near Brasov, Amlas and Farags are not far outside Sibiu, to the west and east respectively. The Faragas range lies directly above Curtea de Arges on this map, and the Piatra Craiulu are just south/southwest of Brasov. Targoviste is Vlad’s capitol, and he built his castle just north of Pitesti)

Wallachia and its greater geography, the southern Carpathians and the southeastern Danube river basin, has been a land of great upheaval, strife, and violence going back at least to the time of the Roman Emperor Trajan, who conquered it in 101 AD when it was known as Dacia, and brought back its riches, including many Dacian slaves, to Rome. Not only was it the last province the Empire would ever conquer, it was the first it would abandon, in 275 AD. Open to incursions from Barbarians who lived north of the Black Sea, in modern Ukraine, Rome pulled back to the Danube, which served as a fortifiable border in contrast to the region just north of the river, which was wide open to invasion between the southeastern corner of the Carpathians and the Danube Delta.

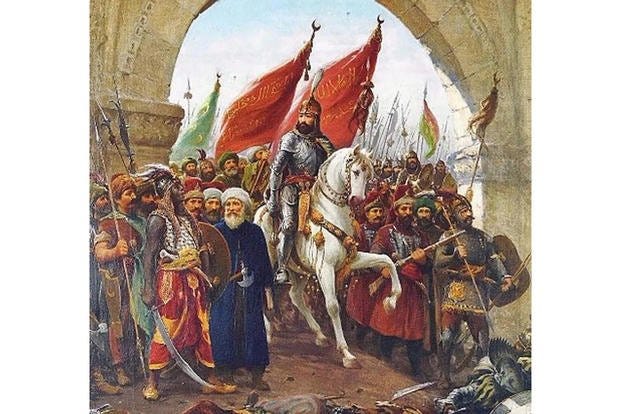

This, in fact, is exactly where the Gothic Barbarian incursions into Rome took place in 376 AD, which led to the Gothic wars and the battle of Adrianople, which ended in the death of the Emperor. A millennium later, Adrianople became what we know of as the Turkish city of Edirne, which became the home of the Turkish Sultan Mehmed II, who conquered Constantinople and renamed it Istanbul. Between the battle of Adrianople fought by the Goths and the Romans and the Turkish conquest in the 14th century, the region was fought over in brutal battles between first the Bulgarians and the Byzantines and then the Bulgarians and the Turks, who also conquered them in the 14th century. Meanwhile Hungary, Serbia, and Moldovia were fought over for centuries among various invaders, factions, and armies, not to mention several crusader armies passing through the western reaches of this region on their way to Jerusalem.

By the time of Vlad III Dracula’s birth, Serbia and Bulgaria, to Wallachia’s west and south, were firmly integrated into the Ottoman Empire, cutting Wallachia off from the Eastern Orthodox Church, while Hungary had established itself to the north as a part of Western Christendom and aligned with Rome, and Moldavia was intermittently allied with Poland or Wallachia and/or Hungary, depending who was on the throne. Hungary and the Ottomans, for their part, allied with and schemed against or attacked Wallachia directly or through proxies whenever it benefitted them to do so in their ongoing struggle with their real enemy: each other.

Given these circumstances and the political maneuverings we shall discuss, Wallachia must be understood as a frontier region, truly alone in the world as neither a pahsalik of the Ottomans nor a part of Hungary, and therefore was treated like a pawn in the Turkish and Hungarian power struggles. The constantly shifting alliances of all these nations with Wallachia depended upon who they most favored as Voivode against their varied enemies. Vlad would not only be imprisoned by both sides at different times in his life, he was betrayed by all of them, and went to war with them all in their countries and on his own land before his untimely death.

The region of Wallachia got its name most likely from the last Roman governor, Flaccus, before the border was pulled back. The land was known as Flacchia, the Dacians who lived there Flaccians, and this branding eventually morphed, as the theory goes, into Wallachia and Wallachian. However, Byzantine historians over the centuries referred to these people as Dacians all the way up until the 15th century, and they are known to historians today as Daco-Romans. These Byzantine historians report that the Daco-Romans retreated north to hide in the Carpatians for nearly a millennium to evade the repeated incursions of the aforementioned Goths and Bulgarians, among many other barbarians who settled and passed through the Wallachian plains. It was only in the first few centuries of the first millennium AD that the Daco-Romans emerged from the mountains and began to settle Wallachia. Vlad made his home in Tirgovoste and established Bucharest, slightly to the south and East, which became the capitol of Romania and remains so to this day. These were the two farthest southern settlements established by the Daco-Romanians by that time, and indicates their growth in strength, organization, and influence as an independent nation, despite how short-lived.

A competing theory for the origin of the name Wallachia, which may still find its origin in the name of the Roman governor Flacchus, was that because the plain was deserted by its Roman inhabitants it was included in the regions known to Western Europe as populated by Vlachs, or Slavs, the people “Vlachian” and the region “Vlachia.” However, Romanian is not slavic but rather a romance language, and the Romanian people were not slavic but, as we’ve said, Daco-Roman, and if this is in fact the origin of the name Wallachia, it is a misnomer. Furthermore, Moldovia to the east was settled by the Romanians and their leaders were enfranchised and backed by Wallachian nobility, and Moldavian kings or voivodes were often blood relatives of Dracula and the clan of the Dracul. It also means that Moldavia’s people, at least its nobility, were also not slavic but derived from the Romans.

Never-the-less, Vlad was actually born in Transylvania and spent a great deal of his life there. Transylvania, in contrast to the Wallachian plain, was a plateau couched in the Carpathians and stretched all the way to Hungary’s extreme east, where the southern range of the mountains swung dramatically northwest all the way through what is today western Ukraine, southern Poland, and northern Slovakia. Bram Stoker places Draculas castle in this range, and features the town of Bistriz, where Johnathan Harker stops before heading through the Borgo Pass to Draculas castle, further north and deep into the mountains. While Vlad’s real castle was in fact in the Carpathians, it was on their southern slopes in Wallachia, and it plays a role in his story that illustrates his brutality and uncompromising nature.

For now it shall suffice that while Vlad was in fact born in this region, in the town of Sighisoara, he did not reside in eastern Transylvania while he was Voivode of Wallachia. Bistriz is a real place and to this day retains its medieval buildings and was also a Saxon trading post, though it was farther north than anywhere in Vlads story, and served trade routes to Poland and Russia, in contrast to the towns Vlad ravaged, which served trade with Constantinople and the Turks. Never the less, we see some of Vlad’s real history finding its way into the legend and, while Stoker got the region of Transylvania wrong by at least a hundred miles, it was historically accurate for him to portray Dracula, despite himself, as the scourge of Transylvania.

(Castul Bran, near Brasov and built by Saxons, was incorrectly attributed as Dracula’s castle after the publication of Bram Stokers Dracula)

VLAD II: THE DRAGON

Vlad III grew up in Transylvania with two of his brothers, Radu and Vlad the Monk, though the latter was from a different mother, and had an older brother Mircea from his mother and father who doesn’t seem to have as much contact with young Vlad III as these other two. Still, like the blood relatives on the Moldavian Throne, his relationship with Mircea plays into his later atrocities. Vlad’s father, Vlad the second, lived a life as complicated and full of warfare and political intrigue as Vlad III, however detailing it would bring this history far beyond its intended scope. Suffice it to say, all Wallachian Voivodes were hopelessly caught between the wiles of their Boyars, the Hungarian emperor and his generals, and the Turks. Vlad II had to play the Hungarians and the Turks off of each other, and this eventually led to his death, for neither side was ever able to fully trust him, both persecuting him in various ways to either ensure his allegiance or punish his transgressions.

Germany plays an influential, though not central, role in the history of the Dracul clan, for while Vlad II resided in Transylvania, he was sent to Nuremberg and inducted into the order of the Dracul, translated as the Dragon, and charged with defending the Hungarian Empire against the Turks, which he did. His sons were known as “Dracula,” or “son of the Dragon.” For this service, the Hungarians backed him and later his son Mircea as Voivode of Wallachia, and Vlad aided John Hunyadi, Hungarian general in Transylvania, in battles against the Turks in Serbia and elsewhere.

Unfortunately, Vlad II could not give his undying allegiance solely to Hungary, and he was obliged to pay tribute to Turkey and even travel to Edirne and pledge an oath to the Sultan, Murad II, never to take up arms against them, in flagrant contradiction of his oath as a Dracul. Sibiu, a Saxon town we mentioned earlier and pointed out on our map, was marked by Sultan Murad II as the ideal staging point for war with Hungary, and in 1438 the Ottomans attacked it from Wallachia with Vlad II’s material aid. This, of course, greatly angered Hunyadi and the Hungarians, who no longer felt they could trust Vlad, and they had him replaced as Voivode. All the evidence, much of which we wont have time to get to, supports the position that Vlad II was truly aligned with Hungary, and only supported the Turks begrudgingly, at the point of the proverbial spear. Regardless, Vlad II had gone against his oath as a Dracul.

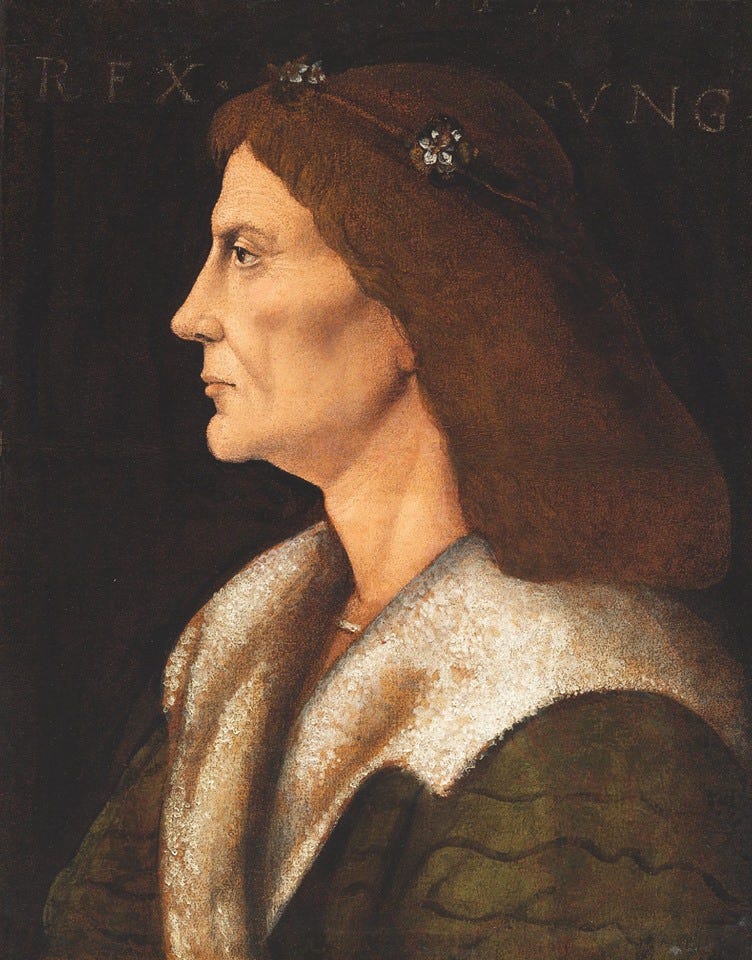

John Hunyadi

At this point, Vlad II had no room to maneuver. War raged between the Turks and the Hungarians, and Hunyadi even repulsed the Turks in one of their attacks on Wallachia, and did battle with them several more times, culminating in the battle of Varna on the Black Sea coast. Vlad II aided Hunyadi in several of these battles, including at Varna, which was on Turkish soil. Because Vlad II began aiding Hunyadi militarily after 1438, the Ottomans had him recalled to Gallipoli with his sons Vlad III and Radu, where they promptly imprisoned all three. They then dispatched Vlad II back to Wallachia with instructions to continue to pay them tribute, cease military aid to Hunyadi, and revert back to a vassal of the Turks. While his two sons, 12 year old Vlad III and 6 year old Radu, were still imprisoned in Turkey, Vlad II reneged on his obligations to the Turks and continued to give aid to Hunyadi, writing these words of resignation in a letter to Transylvania:

Please understand me; I have left my little children to be butchered for Christian peace so that I and my country can be subjects of our king and join with you.

Vlad II’s military aid was never enough for Hunyadi after his relations with the Turks, and at this point Vlad II had even disappeared into Turkey and returned to fight alongside him. Hunyadi could never trust him, though perhaps the last straw was when, after the crushing loss at Varna, Wallachian soldiers helped Hunyadi escape and make his way back to Wallachia, where Vlad II and his son Mircea had him arrested and, at the urging of Mircea, sentenced to death for his failure. Because of his lifetime of achievement in battle, previous good relations, and expulsion by force of the Turks from Wallachia, Vlad II had him released and sent back to Transylvania. As a reward for his clemency, Hunyadi allied with the Boyars against him and had him and Mircea murdered, Mircea in an exceptionally depraved way by having his eyes burned out and then buried alive. All of this while young Vlad III was a prisoner in Turkey.

TURKISH THRALL

By the accounts of the Turks, Vlad was a tumultuous prisoner, endlessly insolent and subject to many whippings and even fights with his guards. Still, he received an education in Turkey, where he mastered the language, had a Greek tutor, learned their ways of warfare, and was exposed to their methods of punishment and torture, which included impalement. In fact, the Turks were notorious for this and employed it regularly, as did many other medieval rulers before, during, and after Vlad III’s reign. Still, Vlad made such frequent and excessive use of it, he became known as “The” impaler for the entire era, even using it against the Turks, as we shall see. Historians speculate that it was his time in Turkey where he learned the methods and developed a taste for impalement.

While impalement was done as a brutal form of execution, it was said to also be an art form and a tactic of intimidation. Some victims would die almost immediately and be left hanging from their pikes to rot and feed carrion as an example to passers-by not to cross the local or imperial ruler, while others were purposefully kept alive by a skillful impaler, prolonging the torture even unto the erection of the pike into the air, where the victim would hang and suffer for hours and sometimes days until he died. The swiftest executions by impalement involved an inelegant two-handed swing of a sledgehammer into the blunt end of a pike, whose spiked end entered the anus and eventually protruded from the stomach, neck, chest, back, or mouth, depending on the angle, and the subject would die of internal organ or vessel rupture before the spike even emerged from his or her other end. A more delicate impalement, often done in the far provinces as a form of example for subjects removed from the Ottoman center of power, was detailed in the novel The Bridge On The Drina, by Ivo Andric, and depicts a Turkish impalement in 16th century Croatia:

without another word the peasant lay down as he had been ordered, face downward. The gipsies approached and the first bound his hands behind his back: then they attached a cord to each of his legs, around the ankles. Then they pulled outwards and to the side, stretching his legs wide apart. Meanwhile Merdjan placed the stake on two small wooden chocks so that it pointed between the peasant’s legs. Then he took from his belt a short broad knife, knelt beside the stretched-out man and leant over him to cut away the cloth of his trousers and to widen the opening through which the stake would enter his body. This most terrible part of the bloody task was, luckily, invisible to the onlookers. They could only see the bound body shudder at the short and unexpected prick of the knife, then half rise as if it were going to stand up, only to fall back again at once, striking dully against the planks. As soon as he had finished, the gipsy leapt up, took the wooden mallet and with slow measured blows began to strike the lower blunt end of the stake. Between each two blows he would stop for a moment and look first at the body in which the stake was penetrating and then at the two gipsies, reminding them to pull slowly and evenly. The body of the peasant, spreadeagled, writhed convulsively; at each blow of the mallet his spine twisted and bent, but the cords pulled at it and kept it straight…at every second blow the gipsy went over to the stretched-out body and leant over it to see whether the stake was going in the right direction and when he had satisfied himself that it had not touched any of the more important internal organs, he returned and went on with his work.

Because Vlad impaled at such a massive and rapid rate, it must be assumed that he did not undertake each in such a painstaking way, and we will see later how he left his victims bodies out on display as a deterrent to future enemies and double-crossers, rather than make the impalement the spectacle we see above. Still, this description gives us a visceral picture of who held Vlad captive, and what he may have witnessed therein.

In any event, rather than sign his son’s death note, Vlad II’s actions actually led to Vlad III’s release in 1448. While Vlad II had betrayed the Turks, Hunyadi was a much more formidable enemy, who had caused far more trouble for them than Vlad II ever had, and they hoped that by freeing Vlad III while holding Radu, they’d have an opponent of Hunyadi and ally of the Turks on the throne of Wallachia once and for all. This proved to be a mistake.

WARLORD OF WALLACHIA AND THE FOREST OF THE IMPALED

Soon after his ascension to the Voivodeship of Wallachia in 1456, Vlad III called a banquet at his residence in Tirgovoste. He gathered together all of the Boyars from around the town, many of whom lived in fortified estates like mini-castles. 500 people were said to be in attendance, lords and their wives, some of whom had been Boyars for decades, with family lines that went back from before Wallachia was a nation. At one point in the dinner, Vlad called for silence and asked all those in attendance “how many Voivodes have you seen in your lives?” After some confused silence, one elder spoke up and said “30.” Vlad went around the room, asking young and old alike. “Seven,” a younger Boyar answered, “dozens” said another. Some even said they weren’t keeping track. While they were giving their answers, Vlad’s men were barring the doors from the outside. One elder Boyar even made reference to Vlads ancestors, two of whom, as we’ve mentioned, were killed by these very Boyars. “Since your grandfather, my liege, I have seen no less than twenty Voivodes.” With this, Vlad gave an order. His men moved swiftly on the Boyars and began detaining them all. We don’t know exactly what happened next, but we may assume some resisted and were subdued violently. Whatever transpired in those first few moments after the soldiers moved into the hall, the result was immortalized in the stories told about Vlad for posterity: every single Boyar was murdered and impaled, their corpses exposed outside his residence to rot and feed the vultures. These were the first victims that became Vlads “Forest Of The Impaled.”

Many, if not all, of these Boyars were either directly responsible for or passively complicit in the removal of his father and brother from power and their subsequent murders. At some point around the time of this massacre, Vlad had his brothers body exhumed to determine whether or not he was really buried alive and, given the fact his body was found buried face down, he determined that he in fact was. This was only the beginning of Vlads vengeance that became a short but atrocious reign of terror. Wallachia did not have a tradition of primogeniture, and as history has shown time and again, this led to instability on the throne and a constant overturning of power. In this case, any son born of the Voivoide was considered legitimate, and all he needed was the support of enough Boyars and, in turn, the Kingdom of Hungary, to be placed on the throne. The fifteenth century was a time of massive overturn, and in one 58 year period there were 29 Voivodes, Vlad III himself taking the seat 3 times, though for extremely short reigns. It was Vlad’s efforts to stabilize this condition and centralize his authority to ensure it in perpetuity that led him to commit a great number of his crimes. And unfortunately for Vlad, most of these actions were in fact seen by outsiders and allies of his enemies as crimes.

The offenses perpetrated against the Transylvanian Saxons were done to this end, for once he massacred his dinner guests, a great number of Boyars fled north and took refuge in the Saxon towns, which welcomed and harbored them knowingly. While there, Vlad assumed they were plotting against him and would eventually attempt to remove him from the Voivodeship. Adding weight to this suspicion was the fact that Dan III, a competitor for the throne, was being harbored at Brasov, one of the towns we mentioned earlier. Furthermore, during his raids, uprisings were staged in Amlas and Fagaras, the two regions that were once in Wallachian possession under Vlads father. Vlad suspected that these uprisings were instigated by the Boyars and Saxons as a way to draw him away, which it did when he went there and suppressed them through burning and mass impalement. Vlad had reason to believe he may soon be subject to similar uprisings inside Wallachia and even an invasion. If he harbored these concerns during his Transylvanian raids, he had very good reason.

But those raids were carried out in 1459 and 60. Two years prior, in 1457, Vlad attacked the aforementioned Transylvanian town of Sibiu, raiding through the village, burning, fighting, and impaling as he went. Though there is no record detailing his motivations, his brother Vlad the Monk was said to reside there, and he was as legitimate a candidate for the throne in the eyes of the Boyars and Wallachian custom as any other brother of his. It should be mentioned that while during these raids Vlad is said to have ridden with 20,000 men - almost certainly an exaggeration - he himself was always at the head of the cavalry, and participated in the raids. In fact, the story goes that Vlad was only able to ascend the throne because he bested his predecessor, Vladislav II, in single combat. At the outset of his Voivodeship and his raids on Transylvania, Vlad was only in his early twenties.

In response to the later raids of 1459-60, Dan III attacked Wallachia. He and his allies, both the Boyars and the Saxons, knew why Vlad attacked, and knew they had to act immediately to neutralize the threat. In 1460, Dan invaded, but Vlad defeated him in battle. In retribution for what his supporters had done to his family, and their future plans on his Voivodeship, Vlad made Dan III dig his own grave. He then had him kneel down in front of it and held his funeral in its entirety while he still lived. It is said that Vlad even had a priest hand him a Bible, from which he was instructed to read a passage. At the end of the ceremony, Dan III was beheaded and thrown into the grave.

Throughout all of these raids, assaults, and massacres, Vlad was supposedly carrying out other mass-executions and changing the rules of trade in Wallachia. The Saxons had grown rich by trading with Constantinople and the Turks through Wallachia, and part of their support for various Voivodes depended on their trade rules and the Boyars who negotiated them. Not only was Vlad attempting to eliminate political opposition by liquidating unsupportive Boyars, he was engaging in brutal trade negotiations with the Saxons when he did things like increase tariffs on them and strictly limit where and when they could sell their goods, and put them to death when they violated these new rules. While again, many historians believe the accounts of the Saxons cannot be totally relied upon as historically accurate and unbiased, they are informative.

One of the ways merchants sold goods in the middle ages, where there were very few stores and trade caravans took months to deliver goods and cash, were merchant bazaars. Sometimes these bazaars took place in foreign lands, and the merchants were subjected to the rules of the local lords and kings. In Wallachia, the Saxons were used to a certain degree of trade freedom because they were often on friendly terms with both the Boyars and the Voivodes in power. Vlad, however, changed the rules once to strictly limit where and when the merchants could sell inside Wallachia during the bazaar. They soon had to make the trek back across the mountains and wouldn’t return until at least the next year, though they couldn’t even be sure, given Vlads actions, if they would ever be back. So they continued to operate outside the designated areas and times until all of their goods were sold. Perhaps intending to all along, perhaps making these rules with this very intention, Vlad had them all executed and impaled.

These are only some of the stories of Vlad killing both Wallachian Boyars and Transylvanian Saxons, but it should be enough to show how merciless, unrelenting, and determined he was to bring these people to heel. He was, as we shall see, also creating very powerful and well connected enemies. If Vlad was massacring so many nobles, the very people traditional feudal societies depended on to produce men at arms for their wars, one might wonder where Vlad found men to form an army. All this time, while Vlad was raiding villages and killing nobles and merchants, he was pillaging and confiscating their wealth. He not only used this wealth to enrich himself, but he also distributed among his men, a great number of whom were initially peasants and locals. As one might imagine, this made them violently loyal to him. Vlad was a true warlord in every sense of the word.

Vlad also moved his residence outside Tirgoviste to a newly built castle, known as Poenari. Poenari was abandoned not long after Vlad’s death and left in obscurity. Eventually, people even forgot that Vlad had lived there. Like the location of the fabled city of Troy, historians eventually located Poenari by asking locals where it was. What they found, atop a steep and somewhat remote foothill in the Carpatians was little more than a foundation and a ruined wall. At one point over the centuries, an earthquake hastened what time had already been doing to the keep. In true Vlad fashion, construction of this castle adds to his terrible legend.

(Poenari Castle)

You see, when Vlad held his banquet, the entire families of the Boyars responsible for his father and brothers deaths were not in attendance. Many of the women and children remained at home, where Vlad had them arrested and forced into labor to build this castle. There are over 1,000 steps up the mountain to the castle, and one marvels at the thought of women and children hauling stones up and stacking them by hand. Needless to say, a great number of them died before the castle was completed, and any survivors were executed. All were added to the forest of the impaled.

During this time, Vlad was attempting to keep good relations with the king-in-waiting of Hungary, Matthias Corvenus, who was positioned to ascend the throne when the previously mentioned general, John Hunyadi, died of the plague the same year Vlad became Voivode. While Vlad was killing his nobles and attacking and plundering Transylvania, he also halted payment of tribute to the Turks. It appears he stopped payment in 1459 and withheld tribute for three years, though he may have made one last payment in 1462, but the Turks had already been pushed too far. Payment of tribute to the Turks involves more than just money, for as we’ve already seen it comes along with oaths not to take up arms against them, and also involved a supply of livestock, grain, and young boys to be raised as soldiers for their army of castrated slaves. The ceasing of payment implied that Vlad was also reneging on his agreement not to take up arms.

(Matthias Corvinus)

We cannot ever truly know what Vlad was thinking when he attacked villages inside Hungary and disobeyed direct Turkish orders, especially when he was viscerally aware of what either side was capable of and willing to do to insolence and disobedience. Vlad was not nearly as powerful as either empire, and there was no hope of him ever becoming so, no matter what he did and how much time he had. Some try to portray him as a cunning, Machiavellian ruler who used intimidation and violence as a tactic of political negotiation, with lofty long-term goals of centralizing power and establishing the legitimacy and stability of Wallachia for posterity. Others portray him as a bloodthirsty villain who wantonly impaled people because he was simply evil and he enjoyed it. We have to consider a third possibility, one that satisfies my historical curiosity and interest in the man, and finds precedence all throughout history.

Vlad might be considered as something of a brigand, pirate, or reaver, who used his position to amass a following and used them in turn to enrich himself, but also take revenge on his enemies. As such, he was beloved by the peasants of Wallachia. He was said to be popular among them, and he did in fact free many of them from the lordship of their Boyars and enrich them and give them jobs as his soldiers and executioners. This time period was rife with peasant upridings and rebellions, many of them sparked by Boyars who used them opportunistically, and it was these uprisings that it was said inspired the Boyars to live within fortified estates. Perhaps Vlad thought he was untouchable, didn’t concern himself with the consequences, or cared more about revenge and slighting his enemies than he did about long-term victory over them. If he was plotting something, and had an end goal that involved himself and his heirs remaining on the throne for years to come, it can be considered as no less than a suicidal gamble. We must consider the possibility that Vlad saw the only chance for the survival of Wallachia was to provoke the Turks and the Hungarians into a war with each other, either hoping for their mutual destruction or to side with whomever was the winner.

Vlads religious allegiance was always to the Eastern Orthodox church, whom he gave money and lands to, sending some all the way to Mount Athos in Greece, but most of it remained within Wallachia. He was known to study religion with Stephen, his cousin and ruler of Moldavia, in the time prior to his Voivodeship, and even had a favorite monastery on the island of Snagov. Perhaps Vlad saw aligning with Hungary as preferable because they were Christian, though Catholic, but absorption into the Ottoman Empire as a tolerable outcome because they allowed their subjects to practice Eastern Orthodoxy, to a degree. This theory seems tenuous, especially when considering Vlads heavy-handed trading tactics with the Saxons, which included but was not limited to outright murder, while for their part the Hungarians allowed them to ply their trade inside their borders unmolested. He also must have known he stood absolutely no chance against the Turks without aid from Hungary, who he was actively committing crimes against.

We cannot be sure of his motivations or if it was the playing out of a long-term plan, but once the Turks finally decided to address his past-due tribute, Vlad did in fact try to get these two sides to go to war.

VLAD THE CRUSADER

In 1461, Vlad sat upon his throne at Poenari and received two Turkish envoys. They discussed his past due tribute and invited him to Constantinople to negotiate repayment and future terms. They were not the first to do so, nor would they be the last. However, Vlad had either grown annoyed with the stream of envoys, or perhaps he felt his message wasn’t getting through by repeatedly sending them back empty-handed. Either way, Vlad decided to make his message clear this time.

“Why do you not remove your turbans when you come before me?”

“My Lord, it is our custom and law.”

“Ah. Allow me to assist you, to better observe your custom and adhere to your law.”

With this, he had the envoy’s turbans nailed to their heads with iron spikes and sent them back to Constantinople with “brain hemorrhages.” This, however, was not the act that finally provoked the Turks to war. They next schemed to trap Vlad and have him abducted and forcibly returned to Constantinople as their prisoner. But this was Vlad Dracula, The Impaler, and the Turks would have to work much harder to bring him in and take over his country.

The next time they visited Vlad, in 1462, they sent a learned Greek scholar skilled in rhetoric and persuasion to ply him with promises of riches and rewards, which included possession of cities or entire regions. Meanwhile they secretly plotted with Hamza-beg, possessor of territory south of the Danube in a region known as the Istru, and governor of the city of Nicopolis, where the Europeans had once invaded in a failed crusade. Once the Greek convinced Vlad to come to Istanbul, Hamza-beg was to attack them and capture Vlad, bringing him to his destination as a prisoner. This time, the Turks were not sending a faceless envoy that Vlad could abuse at will, but an important scholar directly from the Imperial court in Istanbul. This was meant to signal to Vlad that they were ready to appease him, which was of course a ruse, and Vlad knew it immediately. Instead of mulling over the terms and pressing for a better deal, Vlad began preparing for war.

He agreed to accompany the Greek and his party to Istanbul, knowing he had no choice either way, and embarked upon the journey with some of his men. He had a second contingent of mounted soldiers shadow their progress from a discreet distance. Before Hamza-beg sprung the trap, Vlad took the Greek and his men prisoner and, once Hamza attacked, Vlad and his secret guard had him surrounded and taken prisoner, and all the Turkish captives, said to number 1,000, were marched back to Tirgoviste. Vlad proceeded to the Fortress of Giurgiu, on the Romanian side of the Danube but recently taken by the Turks, due south of Bucharest. Vlad and some of his men dressed in Turkish garb, thus disguising the fact they’d neutralized their entourage. Approaching the fortress, Vlad called to them in perfect Turkish, announcing who they were and commanding them to open the gates to prepare for passage to the capital. The Turks complied, and once inside, Vlad and his men attacked, killing all and setting the fortress ablaze. For their part, Hamza-beg, the Greek, and their contingent of Turkish soldiers were added to the fortress of the impaled.

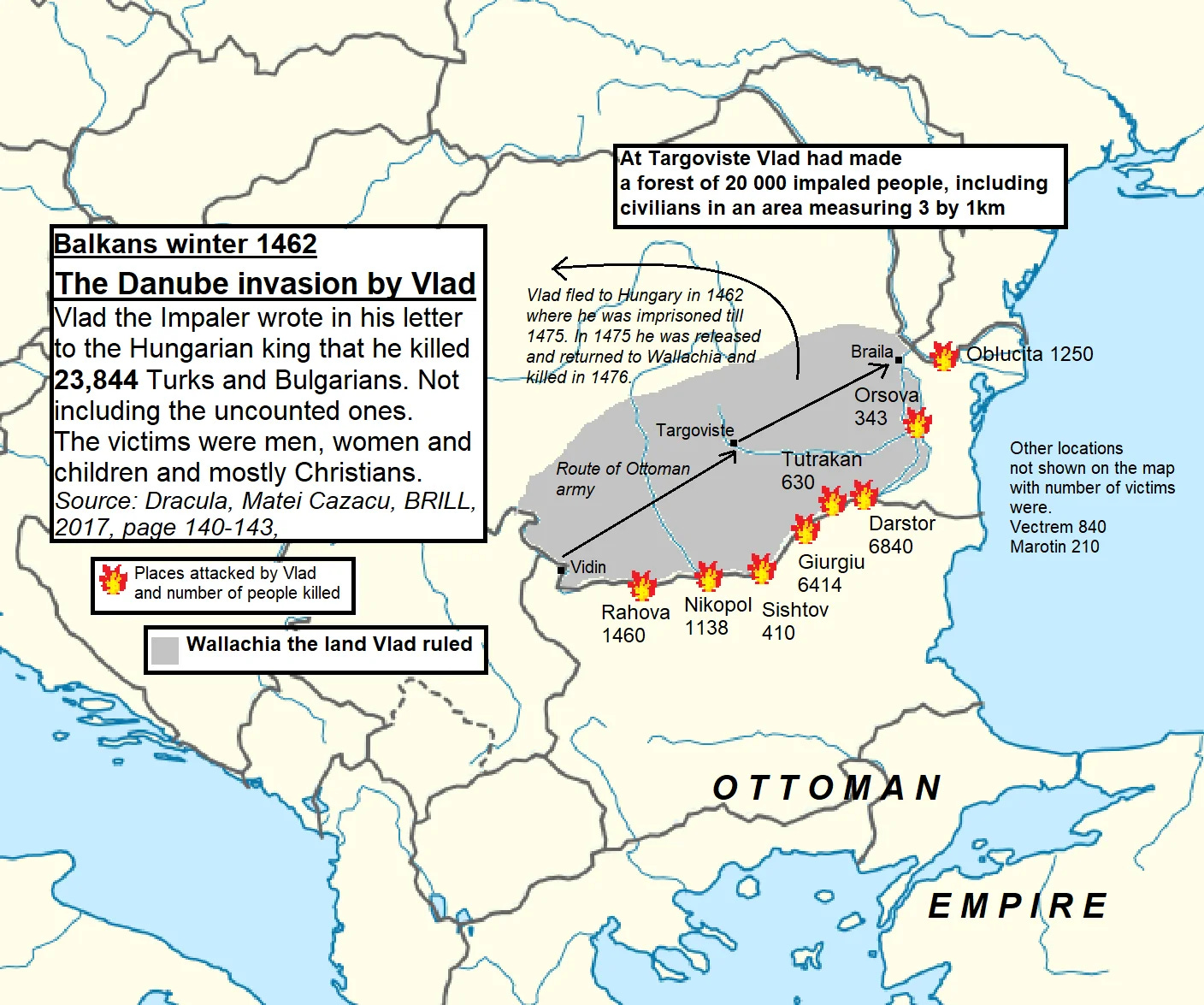

Next, Vlad called his army to his position and crossed the Danube into Ottoman territory and wrought destruction across the Istru and along the southern banks, carving a path of fire and death all the way to the Black Sea. He sacked fortresses, pillaged, plundered, and burned any settlement, port, stronghold, or city he came across, killing all in his path: soldiers, Turks, Bulgarians, men, women, the elderly, and children. In a letter to the Hungarian Emperor he told of his deeds, claiming to have killed over 20,000 Turks, announcing “I have broken the peace.” Along with this letter and somber announcement, he sent a bag of Turkish heads, noses, and ears.

(This map shows the path of the Danubian campaign as well as the subsequent Turkish invasion)

When he made it to the Danube detla at the Black Sea, it is presumed he came in sight of the Ottoman flotilla sailing for the Danube to launch an attack. Whether Vlad came within sight of this fleet we cannot know, for he does not write of it, however there was a fleet that sailed from the Bosphorus to the delta and up the Danube to Vidin, pictured above, whence they launched their attack that summer. Mehmed II, the very Sultan who conquered Constantinople less than a decade prior, accompanied this invading force. Vlad, knowing they would assault Tirgoviste, rode back to Wallachia to make preparations for war.

These preparations were not defensive in nature, but rather evasive. He did not have enough men to stand and fight with the Ottomans, nor was Wallachia populated by a series of defensive forts, castles, or walled cities. Even if it was, the Turks had already proven the futility in this, for Constantinople was considered the most impregnable city not just in the world at that time, but in history. If a city a millennia old could not withstand the Turks, what could a tiny principality like Wallachia do? Scorched earth was the only move Vlad had. Therefore, he poisoned all the wells in a wide swath between Vidin and Tirgovieste. He burned crops in the field. He evacuated the entire population, leaving a series of ghost-towns, and hid the people and the livestock in the marshes, forests, and mountains. Any cattle or other animals they could not bring, they butchered and left to rot in the sun. Vlad then rode to Vidin to meet with the Turks.

Despite the futility, this is the only time Vlad launched a frontal assault on the Turkish army. The ships were only able to cross the Danube a few at a time, and when on the other side, disembarking was a long, tedious process that left the army exposed. This is when Vlad attacked, forcing the Turks to set up a defensive position, slowing them down. The Sultan watched as the Turks began to fire cannon at the Wallachians, and the Wallachians fired back, despite being significantly outgunned. Eventually the Turks realized that they couldn’t cross at all without fully fortifying their position, which they did by digging trenches, throwing up massive pikes to repel Vlad’s repeated cavalry charges, and positioning cannons to fire from within their redoubt. It must be stressed that for all of these assaults, and for every other action on this campaign prior or subsequently, Vlad himself was at the head of the charge. It is said they slew 300 Turks in this way.

Once the Turks were in position and able to bring the rest of their force across safely, Vlad and his men retreated into the forest, where they remained for the rest of the invasion. The Turks began advancing slowly, recreating their defensive stronghold in the field every night; trenches, pikes, cannon and all. Needless to say, this was an arduous task. This tactic, of digging trenches every night, was a tried and true practice for any invading pre-modern army, and was in fact Caesar’s habit in Gaul. It required a vast amount of resources in both manpower and supplies, in addition to marching all day, carrying equipment, setting up and breaking camp and, of course, fighting. Soon, the lack of water and food would catch up to them. The sources do not mention a baggage train back to Vidin and into Turkey, but if there was one, it was not enough to supply the army as it advanced.

Vlad and his forces spent this entire campaign hiding in the woods, much of it dense old growth oak, difficult to navigate on horseback, especially for those unfamiliar with the terrain. The Wallachians knew it well, and used it to their advantage. Any expeditionary forces sent out by the Turks to search for Vlad, supplies, water, or to pillage, were all cut down to a man. Eventually, the Turks stopped sending them out at all. However, a frontal assault was unthinkable, so Vlad decided to take a measure that military tacticians of the Medieval and Ancient world agreed was folly and desperation: a night attack.

Vlad had no hope of winning a war of attrition, and no interest in waging one. Instead, his only chance was to kill the Sultan, and a night attack was the only way he imagined he could accomplish that. The plan was to make a run for the Sultans tent, cut through his guard, kill him, burn the tent, and get out. To any reasonable observer, this was suicide. But the Turks were already in Wallachia, victory was impossible, and Vlad had opportunities to run away every single day. This was what he chose. By the time he made this decision, June 17, the Turks had already been rampaging around Wallachia, rather aimlessly, and were camped outside Tirgoviste. Numbers for each side vary, I’ve read as few as 22,000 for Vlad, but the largest number at 29-30,000. The smallest number I’ve seen for the Turks, however, was 60,000, but they go as high as 100, 120, and even 200,000. Even with Vlad’s number at the highest, and Mehmed’s at the lowest, the Wallachians were outnumber 2-1, and their cannon were veritably useless against the Turks, whose cannon division was the largest in the world.

One chronicler from inside the Turkish camp writes a detailed account of the attack. Nighttime duties went on as usual, with a muffled din of pots and pans being cleaned up from dinner, a few soldiers on duty pacing about, others chatting quietly, and little coming and going of people who either couldn’t sleep or were awake fulfilling duties. Many had gone without water for days and a had lobbied complaints about unabated thirst. Amidst the routine goings-on, an owl hooted. Then another. This was Vlad’s signal.

Chaos erupted. No one one knew where the attack was coming from. In fact, many did not even know they were under attack right away. At first, Vlad and his men rode into the edges of the camp and began cutting people down, seemingly at random. However, the got themselves organized very quickly. Within minutes, the Turks began to see Wallachians with torches riding to and fro without attacking anyone. Soon, they heard horns blowing. This only increased the sense of chaos for most, but a few knew what was happening: they were signaling to each other. And they could only be signaling one thing; the location of the Sultans tent. Unfortunately for Vlad, they identified the wrong one. Bringing the full force of their assault down on this tent, they completely destroyed it, killing the unorganized guard and two military wazirs inside. This was effective in its own right, but the mistake caused the failure of the raid, for while they were butchering the people in and around this great tent, the rest of the Turks were forming up around the Sultan.

Once Vlad realized that they’d gotten the wrong target, he looked around to assess the situation. There was no missing the Sultans tent now, for it was circled by Turkish forces, several men thick with pikes sticking out everywhere, firing volleys of arrows. The Wallachians would never get through. The Turks, for their part, would not break formation to attack, lest some of the Wallachians get inside. Vlad knew he had lost the night. One account claims a boyar of his was supposed to attack the camp from the other side and form a pincer on the Sultans position, but whether this was true or not, no other forces joined Vlad that night outside the Sultans tent.

By this point it was very late, only a few hours before the dawn. In full view of the Turkish forces, the Wallachians began wantonly butchering their pack animals, which made strategic sense in that it would hinder the Turks continued march through his country, but also may have been done purely out of frustration and spite. Regardless, after many animals were cut down, Vlad and his men rode off into the darkness. Some chronicles report that few casualties were taken by either side, while others say Vlad lost at least 5,000 cavalrymen, the Turks 15,000 soldiers. These numbers can’t be right, for Vlad to lose a fifth of his cavalry in one night while his enemy lost only maybe 10% of their infantry would constitute a devastating loss for the Wallachians. Still, he had just survived a suicide mission, and this assault alone would have earned him at least a passing mention in the history books of Medieval warfare.

One cannot know how long Vlad would’ve had the will to keep this up, but it appears he had the resources and maneuverability to go on much longer than the Turks. Despite this, no amount of time led to a victory for Wallachia unless Hungary joined the fight. As we shall soon discuss, they did not. The Turks had the numbers to fight in perpetuity, but what they could not do was continue to drag 60-120,000 men without food or water around a foreign country. The last straw for them came very soon after the night assault. As they approached Tirgoviste, they came upon Vlad’s fabled “Forest of the Impaled.” The number of corpses given for this scene is 20,000, and it was said to be two miles long and one mile wide, circling the city. It is also said that to this day, a tower stands in Tirgoviste whence one could stand and survey the entire forest. Though the accounts claim these were all Turks, this cannot be true, for we know Vlad had impaled a great number of others as well. Still, he had been killing Turks all summer, sending many of them back for impalement, while they had killed very few Wallachians, and this was the last piece of demoralization they were able to withstand.

The corpses were in various stages of decomposition, and the horror of the scene is difficult to imagine, though some chroniclers of the time attempted to convey what the Turks walked into that day. Many had decayed into skeletons, and I would imagine some of the pikes must have been empty for the corpses rotting completely away. Others were picked over by carrion, with strips of flesh hanging down, bones exposed, half removed scalps and tattered wisps of clothing stringing in the breeze. Some of the details are truly horrific, and defy the imagination. Mothers impaled beneath their babies on the same pike, other women with great cavities carved out of their chests where their breasts once were with their babies stuffed inside. There were others with hollowed out chest cavities in which birds, probably crows and vultures, had made nests. Some observed vultures feeding on the faces of the corpses.

The stench cannot be described in words, but we must remember whatever the smell was, it was hitting men who’d been marching in the hot sun for a month, and had gone days without water, longer without food, had seen their comrades slain or disappeared, and they themselves had been fighting off mounted riders for weeks. It is probably safe to say some began retching, their empty stomachs convulsing and doubling them over to dry heave in the hot sun. The stench of the forest of the impaled was a thing of legend, for one report of Vlad’s misdeeds claimed that a man once complained of the smell and asked Vlad how he could live like that. Vlad was said to have impaled him on an extra tall stake, telling him he would be suspended so far above the other corpses that he could catch a breath of fresh air and be free of the stink.

In any event, this scene was enough for the Turks. One cannot say they retreated exactly, for while Vlad had continually harried them every step of the way, he did not induce any militarily significant casualties. His harassment, his scorched earth tactics, and his forest of the impaled was enough for the Turks to give up and be on their way. They quickly vacated Wallachia with Vlad on their heels all the way, and it appeared for a brief time that Vlad had rid Wallachia of the Turks. Not only was that far from the truth, there were worse things to come for him very shortly, things that we have no evidence he foresaw but, with the gift of hindsight and the birds eye view we have of his neighbors and their schemes, he should have.

A MAN ALONE

Vlads campaigns in Transylvania and his war with Turks took place over only 3 short years, while there are European kings you’ve never heard of who had 20-30 year reigns. Although Vlad is only known worldwide because of Bram Stokers novel, the novel could only have been written because he cast a shadow over Transylvania that persisted for almost 500 years. While his deeds were excessively brutal even by the standards of the day, they must not be seen as the actions of a bloodthirsty murderer, nor the crusade of a hero of Europe. Rather, they must be taken for what they were; the maneuvering of man with no real power, no real allies, and no real options. Any course taken would’ve produced the same results: Vlads removal from the throne, death, and the loss of Wallachia to the Turks.

When the Turkish army returned home, they left behind another man who’d been on the campaign: Vlads brother Radu, known by now as Radu the Handsome. He lobbied the Boyars, with the backing of the Sultan, to turn against Vlad and install himself as Voivode. He had an easy time convincing them that Vlad would only bring them more trouble, more of the same, and with him on the throne relations with the Turks would greatly improve. The Boyars instantly agreed, in fact some were reported to have fled to Hungary the day after the night attack, and had Vlad deposed and replaced with Radu. With this, Vlad fled to Transylvania. Once there, Corvinus had him arrested and thrown in prison for the crimes he committed in Transylvania against the Saxons and boyar refugees. Vlad would remain there for the next 13 years.

During all these events we’ve discussed, the Hungarians, Turks, and Moldavians were all making agreements with each other that did not include Vlad. The Transylvanians wanted favorable agreements that allowed them to trade in and across Wallachia. They saw Vlad as unreliable and unfavorable to their priorities. The Moldavians wanted protection from the Turks and their own favorable trade agreements, which Vlad was unable to provide, so they appealed to the Hungarians. They were also vassals of Poland and needed to play Poland, the Hungarians, and the Turks off of each other the same way Vlad was trying to do. Meanwhile, the Turks were likewise negotiating trade agreements and armistices with all of them against or without Vlad. In the midst of all this, Vlad was using heavy handed tactics to exact revenge, force favorable trade conditions for himself, and provoking the Turks to war. There was one other factor we haven’t mentioned that played into Vlads decisions.

In 1459, Pope Pius II began making preparations to call a new Crusade to halt Turkish advances in the Balkans and in reaction to the loss of Constantinople, which had served as a bulwark against Ottoman expansion into Europe for centuries. At this time, politics across Europe had grown contentious and many leaders were deeply embroiled in their own affairs and were on very bad terms with Rome. The Pope called a congress to prepare for the official Crusade, but England was fighting the War of the Roses, France was not on good terms with the Pope, who backed a bastard son - and therefore pretender - for the throne, and the Holy Roma Emperor sent Gregory of Heimburg as representative to the congress. Gregory had been excommunicated, and while he promised over 40,000 troops, he was said to be openly hostile to the Pope and these troops were never sent. Poland, the sometimes overlords of Moldavia, were also deeply engaged in a long war and did not commit troops.

The Hungarians were themselves deeply involved in a power dispute, one that affected Vlad and may have played a role into his actions against the Turks. Earlier we referred to Matthias Corvinus as the “king-in-waiting” in Hungary because the country was deep in civil war over the throne. You see, Corvinus was the second son of John Hunyadi, the man whom had Vlads father and older brother murdered and had supported a rival Wallachian faction to take the throne. This is the faction Vlad attacked so brutally in Transylvania. When Hunyadi died, Corvinus was next in line, but he was only a child. In addition, the Holy Roman Emperor backed another man for the throne . Civil war raged for years in Hungary, with Corvinus lobbying for the support of various factions within the empire to help him take the throne from the pretender. One very important faction, whose support was seen as critical in this dispute, were the Transylvanian Saxons.

In 1460, Matthias Corvinus’ uncle, Michael Szilagyi, was captured by the Turks and sawn in half. Szilagy was a powerful man who had not only gave Matthias invaluable support by providing thousands of troops in his struggle for the throne, but he convinced the nobles of Hungary to elect him king in 1458. Szilagyi was a friend and supporter of Vlad Dracula. In the years prior to his ascension to the Voivodeship, as we’ve mentioned, Dracula lived in Transylvania. He spent much of his time there in the company of Szilagyi and Stephen the Great, eventual king of Moldavia. When Szilagyi was killed, suddenly Vlad lost his only ally in a country whose king owed his power to people who Vlad had recently abused in such historically brutal ways. Vlad’s response to this was to draw up new trade terms for the Transylvanian Saxons, terms that were incredibly favorable to Brasov in particular. Not only that, the next envoys the Turks sent to collect their tribute were the very same ones who Vlad had nails hammered into their skulls. Vlad made sure to write a letter to Hungary letting them know of his deed.

These events should all shed light on Vlads decision making. His actions in Transylvania were against an Empire whose powerful merchants were actively opposing his rulership of Wallachia, and his actions against the Turks were, in part, an attempt to garner favor with the very people he had so egregiously attacked that very same year. While the Pope was unable to raise an army, he was able to raise money, which he gave to Corvinus. Vlad took a gamble, appealing to God, the Church, and the King, to come to his aid. In the same letter mentioned above, in which Vlad announces he has “broken the peace,” and sent heads to the king of Hungary, Vlad appealed to them for military aid. Recall that this letter was sent after Vlad escaped a Turkish trap and attacked, burned, and murdered Turks all along the Danube, but before the Turkish invasion.

Your majesty should know that we have done all we could, for the time being, to harm those who kept urging us to leave the Christians and to take their side. Therefore, Your Majesty should know that we have broken our peace wit them, not for our own benefit, but for the honor of Your Majesty and the Holy Crown of Your Majesty, and for the preservation of Christianity and the strengthening of the Catholic faith. Seeing what we did to them, they left the quarrels and fights they had up to now in other places, including the coutnry and Holy Crown of Your Majesty, as well as all other places, and they threw all of their strength against us. When the weather permits, that is to say, in the spring, they will come with evil intentions and with all their power.

Vlad was correct. The Turks attacked “when the weather permitted,” but the Hungarians did not send aid. Vlad’s appeals to “Your Majesty” and the “Catholic faith” did not move the king, whose greatest and wealthiest supporters told horrific stories about this man, and had a part in the murder of his family and usurpation of his throne. Besides, despite the oath of the Dracul, the Wallachians and Vlad himself were traditionally Eastern Orthodox, so the appeals to the Catholic Church must have been suspect, if not laughable, to Matthias Corvinus.

The reality may be that the Hungarians all along saw the southern Carpathians as a natural barrier against the Turks, and only found Wallachia useful for as long as they served as a buffer. But with Vlad committing historically brutal atrocities on their land, it must have been quiet easy for the Hungarians to sit idly by while the Turks did what they may have considered their dirty work for them. To look at it one way, by refusing to send aid, all the Hungarians had to do was wait for Vlad to flee to their lands and arrest him, rather than have to invade and capture him. We can’t be sure why Vlad provoked the Turks the way he did, but it looks like he was trying force Hungary into supporting him by creating a threat he couldn’t make on his own, in hopes of compelling the Hungarians to overlook his recent transgressions.

One other battle during the Turkish invasion of Wallachia deserves discussion, for it serves as an example of just how bizarre, complicated, ephemeral, and even paradoxical these alliances, oaths, and agreements were between all the forces Vlad had to contend with. One of the walled ports on the Danube Delta was Chilia, its fortress on the Wallachian side. This fort was so far east it was just south of Moldavia, and was considered of vital import to the Moldvians as a staging and entry point for any possible Turkish invasion, not to mention a well-positioned trading port at the mouth of the Danube. The Moldavians in particular saw it as vitally important to their independence from the Turks, but while the fortress was technically on Wallachian territory, it had been garrisoned by Hungarians since John Hunyadi took it over in 1448 to settle a dispute between the Moldavians and Wallachians, who had been fighting over it for decades.

Now, while Vlad was contending with a massive Turkish army on his land, Stephen rode on Chilia and attempted to take it from the Hungarian garrison. Remember, technically when the fort was occupied by the Hungarians, it was Wallachia’s possession and they were allies at the time. Ostensibly it remained so, despite the souring of relations between Hungary and Wallachia. Either way, Vlad saw the fort as his, and split his army to keep Stephen back, sending as many as 7,000 cavalrymen. One might be tempted to say this was a terrible decision, but his fight against the Turks was hopeless anyway and perhaps he thought he could at least hold on to this outpost. The Turks began to withdraw from Wallachia, however, and Vlad was able to turn Stephens attack away after only a few days without much loss of life recorded.

Several accounts of this confrontation raise some interesting alliances here. The Ottomans and a Byzantine historian claim that Stephen attacked Chilia on the Turks prompting as part of their attempt to take over Wallachia. If this is true, it would mean the Wallachians and the Hungarians fought against the Turks at Chilia, but the Hungarians refused to send reinforcements to Vlad at Tirgoviste to expel the Turks from his country. The Hungarians at Chilia were trapped, and had no choice but to fight, and one imagines Vlad happy to have any help he could get, especially after splitting his forces. The Moldavians, however, were constantly angling with the Hungarians and the Poles against the Turks, so fighting on their side against Vlad would’ve put them in a contradictory position from their standpoint, for Chilia was much coveted by the Turks, and Stephen must have assumed that, were they successful, the Turks would instantly try to take it from him.

However, Moldavian historians assert that Stephen attacked Chilia opportunistically to take it from Vlad and the Hungarians while they were otherwise occupied, and that the Turks only retroactively took credit for this attack. Either way, it would prove a bittersweet victory for Vlad, not only because he would soon after be arrested by the Hungarians, but because Stephen was his cousin. While Vlad was in Transylvania as an adult, after being freed from the Turkish prison but before becoming Voivode, he spent his time mostly in the company of Michael Szilagy and Stephen of Moldavia. During this time, Vlad not only studied Eastern Orthodoxy with him, but he also helped him take the throne of Moldavia. A pretender was on the throne while Stephen was in Transylvania, and once Vlad took the throne of Wallachia, he sent troops to Moldavia to help unseat the illegitimate king and put Stephen in his place.

So now, Vlad had not only seen his only ally in Hungary sawn in half by the Turks, not only had the Hungarians left him to defend his homeland alone, despite having agreed to a crusade with the Pope, Vlad had now been betrayed by a cousin and supposed ally against the Turks whom he had helped become king only five years earlier.

CONCLUSION

I have tried as best I could to emphasize how hopeless Vlad’s position was from the start. The story of Wallachia and Vlad the Impaler is really only a footnote in the story of Ottoman expansion into Europe that went on for another two centuries. Both Wallachia and Moldavia would eventually fall completely to the Turks by the early 16th century, continuing to fight over Chilia all the way. The southern carpathians would serve as a natural border of Europe, and while we only barely scratched the surface of Hungarian-Wallachian relations in this essay, it is very clear through the dizzying changes of treaties and attitudes between the two nations that after Hunyadi, the Hungarians were happy to allow the Turks to have their transCarpathian neighbors.

Given this state of affairs, my hope was to convey that it didn’t matter what Vlad did. Had he treated the Transylvanians with clemency or diplomacy, they would’ve still turned on him and Vlad would’ve probably had to fight a civil war with the Hungarians backing the other side. If it came to this, and he chose to allow the Turks to back him, then all the rumors that had been spread about him and his father would’ve instantly proven true: they were working with the Turks against Hungary. Vlad would always be the son of the man who attacked Sibiu with the Turks and put Hunyadi, the father of the current king, on trial and sentenced him to death.

Once Vlad got out of prison, he ended up not only fighting, at the behest of the Hungarians, on the side of the Moldavians against the Turks, he was briefly reinstated as Voivode. This only lasted a few months, for he was killed in battle and his head sent to Constantinople. This was always going to be his fate. Edirne, the capital of the Ottoman empire, was only 250 miles to the south, across wide open plains (and the Danube), while the capital of Hungary was 400 miles north, across the mountains. The Hungarians felt no ethnic or religious bonds with the Wallachians, and until the German stories and woodcuts emerged, most Europeans beyond Hungary probably had no idea he or Wallachia existed.

Vlads short reign was one of pure defiance. We really cannot know if he was thinking several steps ahead, playing one force off the other, angling for position, or attempting to secure his throne for generations. There is a real possibility, I may even say likelihood, that there is nothing Machiavellian about Vlads actions. I choose to see Vlad as a reaver, a barbarian in the ancient sense of the word: uncultured, violent, and existing wholly outside the social order. This is quite literally true of Vlad, who was caught between two civilized superpowers and lashed out at them from a position that was futile both in arms and influence.

As soon as Vlad ascended the throne, the very first thing he did was take revenge for the killing of his father and brother, and attempt to take back the land stolen from him by a much richer, stronger, and better-connected force. In so doing, he built an army from almost nothing, from the ground up, by reaving across foreign lands and plundering their wealth. He then took this self-made army to attack his neighbor on his other border, knowing full well this would bring the most powerful army in the world against him. My contention is that Vlad simply didn’t care. He didn’t care about death, he didn’t care about his legacy, and he didn’t even care about Wallachia. All that mattered was that while he had the power to strike his enemies, he would make them bleed.

And it worked. Although Wallachia was doomed from before he was born, the world never forgot the name of Vlad III: Dracula.

POSTSCRIPT: A NOTE ON SOURCES

The vast majority of the information in this essay was taken from four sources. If one were to amass a small library on Vlad the Impaler, one might note that they all reference each other, yet they also contradict each other at times. Some will vaguely brush over an episode and dismiss it as lacking in primary sources, while others will go into great detail about this same scenario.

Were I a true historian, I would’ve sussed out in writing what was true, what was incorrect, and what was speculation. Very often these spurious details and incorrect facts come from later, but still medieval, historians. I would then have presented all different angles and tried to find the truth somewhere in the middle. However, that would’ve required an entire book. I am telling you now to inform you that if any version of events was recounted in one book, but a much different version was given elsewhere, I simply left it out.

However, my hope is that this article will inspire some to look further into the life of Vlad III Dracula and read more about him. I ALSO hope that this article will satisfy the curiosity of the great majority of readers, and I assure you that if you enjoyed this article but decided against looking elsewhere, you’ve been treated to not only the most important and exciting facts of Vlad’s life, you’ve also been given a sufficient overview of the geo-political/socio-historical conditions on the ground as they existed for Vlad and his contemporaries, as well as some well-informed speculation on the motivations behind some of his actions. In fact, I contend this is the best one-stop resource on Vlad anywhere online that didn’t first appear in a book.

If you would like to read further, here are the sources this article comes from, with a short assessment of each. I WILL NOT link to Amazon unless they pay me, so you’ll have to copy/paste:

If you read only one book on Vlad, in its entirety, it simply MUST be “In Search Of Dracula,” by Radu Florescu and Raymond T. McNally. Make sure you buy ONLY the revised 1994 edition. It contains a number of corrections to incorrect information found in other books of theirs. These men are true historians, in that they travelled all over Wallachia and Transylvania researching, and they are the ones who discovered Poenari castle. The book also delves deeply into the growth of the legend of Vlad the Impaler into the Vampire legend. They sort out the facts from Vlad’s life and the story in Bram Stokers book, and they imbue their story with historical details taken from their vast knowledge not only of the middle ages, but of Romania in particular. Highly readable.

If you don’t want to read an entire book on Vlad, you may want to try “Defenders of the West,” by Raymond Ibrahim, out of print now but available on ebook. The book is about great men who defended Christendom from the heathen Turks, and features a 40+ page chapter on Vlad. This is very readable and exciting, and is the most fluid account of his feats available. Ibrahim leaves out the dizzying, labyrinthine negotiations between all parties involves and tells a lucid, easy to follow story. While I took most of my information and perspective from the previous and next book, I tried to model my essay after Ibrahim in readability. Ibrahim, however, is an Eyptian Christian with quite a bone to pick with the Turks, which is fine. I don’t like them either. It must be mentioned that this book is very biased, and paints Vlad more or less as a Crusading hero. I wish he was, but I’m not sure thats the case.

This next book is for serious scholars or Substack writers only. “Vlad III Dracula,” by Kurt Treptow, is a phenomenal history book, but NOT for beginners. If you want an introduction to Vlad, read the previous two. If you want cross-referencing of a great many sources, various perspectives on the different historical opinions on Vlad, and a detailed critique of disparate accountings of different events in Vlad’s life, then this is your book. For one example only - and trust me, the entire book is like this - for the siege of Chilia, Treptow tells us only what we know for certain happened, and then compares and contrasts the versions given by a Byzantine at the time, a Turkish chronicle, and a Romanian historian writing a few hundred years after the events, and accounts of discussions of Chilia found in Hungarian sources, some of them from decades prior to Vlad’s war. Like I said, this one is for serious researchers only.

Lastly, there was “Dracula’s Wars,” by James Waterson. This book was a much better read than the one above, and solely focused on Vlad and his conflicts, in contradistinction to Florescu and McNally. Think of it as Ibrahim’s exciting, page-turning chapter in book form. It includes quite a lot of regional history and goes into great detail about Vlad’s father and the political machinations of all the empires and kingdoms we’ve discussed. Unfortunately, he favors readability over fact, and I found several details that were either contradicted by other books, or not substantiated in any of the other books I’ve read. Therefore, I cannot in good conscience recommend this book without first reading Treptow, if not Florescu and McNally, though this is the best read of the three. So, if you don’t care about learning incorrect facts, be my guest.

And if you still want more but don’t feel like reading a book, watch this amazing video. Its so good, I almost deleted this whole essay, and while it relies heavily on Waterson, it leaves out some of the worst inaccuracies and even seems, as far as I can tell, to correct one.

This was awesome, the maps really helped understand the concept of what was happening.

Fantastic. I've always found Vlad III and these regional conflicts to be horrifying. The idea that he was a crusader for Christendom has always felt like a revision of history.