This essay was initially going to be an analysis of the film, a refutation of the gay and feminist interpretations, and a discussion of the films legacy, which would incorporate a Nietzschean perspective on the initial analysis. However, the analysis ended up at 5,000 words, so I decided to break it up into parts one and two. At the end of it all, a podcast discussion will ensue.

FIGHT CLUB

The psychoanalytic model of the psyche as delineated by Sigmund Freud has been America's conceptual frame for about a century now. Everything from the analysis of motivations for crime, underlying theories of advertising, critiques of race and gender, and both the creation and interpretation of film and literature are to some extent rooted in Freudian psychoanalysis. This model in its simplistic, popular understanding depicts different aspects of the human psyche compartmentalized and separated from each other, always in tension and under moderation or failing to come under moderation. Those who fail to moderate the competing forces of their psyche suffer from neurosis, a broad term for most abnormal psychology, which basically means they are unable to progress through psychological stages into maturity or stable ego expression. Those who effectively moderate the different aspects of their psyches “individuate,” or establish a strong ego with which they move through the world unphased by outside attempts to destabilize or obfuscate it.

Fight Club personifies these different aspects of the psyche and turns them into characters who dwell in externalizations of the different regions of consciousness. The ego is the “I” that meets the world and navigates the tapestry of other egos and outside forces looking to exert control upon it for their own ends, be it purposeful or inadvertent. The Id is the unconscious that is always latent in the ego but manifests only at certain times, like in dreams, but constantly lurks, potentially coming to the fore and exerting its blind urges over the will of the ego. The superego is the higher conscious faculties that moderate the interplay between the Id and the ego; the intellect suppressing the emotions, if you will.

Clearly, Edward Norton (henceforth “Norton”) represents the ego and Tyler Durden represents the Id. Norton is the one who goes into “polite” society and abides with a very weak sense of self. We see this in his, and later Durdens,assessment of commercial culture. Commercial culture's mode of perpetuation is to “overcode” your ego's sense of self-identification with its own referents for ego identity -“products” - in order to divert your will into an ever-spending consumer. And if you allow your Id - your impulsive desires - to overtake your ego and overpower your consciousness, you are unable to navigate this world and become an effective consumer. That identity is lost, and consumer spending along with it (note that this is not the same thing as marketing appeals to your “lower” self: earning the money requires a strong superego, *spending* the money can be all Id, but that aspect is not in play with the way Norton is depicted spending his money).

An effective super ego will compartmentalize these aspects of your self, allowing the ego to navigate the world while suppressing the Id, but embellishing the Id at times in order to placate it and keep its power in check. But if the Id is repressed too strongly and not allowed to express itself it eats away at or even obliterates your ego. If your ego is too dependent on identification with an outside force, it weakens and the individual becomes either a cowering neurotic or an addictive or violent maladjusted social outcast. All of these states of affairs are in play in the film Fight Club.

Norton had a weak ego, totally identifying himself with consumer culture. This is made explicit throughout the film, most of all in the beginning voice over, where he asks “what kind of dining set defines me as a person?” And we know he’s suffering from neurosis because he goes to group therapy in order to obtain a human connection and emotional release, which affords him the ability to sleep soundly at night. We find out that he is addicted to these therapy sessions and attends a different one each night, which is how he meets Marla, who's doing the same thing.

Now, we must take a moment to consider a few things here before incorporating Durden into the psychological profile of Norton. Norton’s conscious life is represented by his bright, clean, well ordered apartment. This order is the order of his conscious mind over his emotions, but clearly something major is missing. It brings insomnia, which leads to the therapy sessions that allow him to sleep. As I said earlier, dreams are one outlet for the Id or unconscious to exercise its desires, but Norton was deprived of that as he identifies more and more with his consumer products. In other words, his rational mind was suppressing his unconscious and attaching itself to a prescribed identity.

However, this suppression was not just of his emotions or his desires, but of his instincts, specifically his masculine instincts. An instinct is something that cannot be negated, only redirected or, in Freud's term, sublimated. Repression is the attempt to stifle an instinct for one reason or another, and here the director David Fincher wants to drive the point home early that in order to be a good consumer, these instincts must be repressed to the point of inversion. There are feminine images and references all over these scenes, with the sequence of Norton shopping for his apartment and his interactions with Bob at the support group meetings. First, while he’s picking out things to decorate his apartment with, he says he has become a slave to the IKEA “nesting instinct.” While we could argue that the simple act of interior decorating is itself a feminine activity, the “nesting instinct” is something a pregnant woman develops to prepare her home for the expected baby. Norton has repressed his male instincts so much he has deluded himself into believing he has the instincts of a woman.

The character of Bob and his interactions with Norton make this even clearer. Not only does Bob have “Bitch Tits,” but he got them because of an overproduction of estrogen brought on by having his tetsticles removed due to cancer. He then holds Norton to his breasts like a mother would a child and allows him to cry. The men in this film aren’t simply acting like women, they’re becoming women, physically and emotionally. And the only way for Norton to achieve a state of reprieve from the tension of his over-organized way of living is by becoming infantilized and regressing emotionally.

Durdens character is a personification of Norton’s Id, unconscious or, most importantly, his instincts. The masculine urge is to use violence to get what one wants, to take from someone weaker, including sex from women, and to lash out immediately when another man has slighted you. Your super-ego, or conscious mind, overrides this instinct and stays your hand. This is how civilization is able to perpetuate itself, and the “you” that presents itself to the world, that doesn’t rape or bully or commit violence, is your ego. This is Norton. However he has suppressed his urges so much he is becoming like a child, or a woman, and it finally “blows up” in his face when he meets Durden, who blows up his apartment in a terrorist like attack. Norton must then go and live with Durden, whose only stipulation is that he punch him as hard as he can first. Durden is the personification of Nortons repressed instincts.

These metaphors are so blatant they border on heavy-handedness, but it’s handled so well by Fincher that one is able to forget all of this psychologizing and enjoy the movie for its humor, style, and freshness. Fincher lays all the pieces out like a traditional narrative and even with the opening scene hinting at the climax, it’s not until the end when everything falls into place and these psychological allegories become overt. When we first meet Tyler Durden, we don’t know (if we haven’t read the book) that he is another aspect of Norton’s personality.

Durden is Norton’s Jungian “Shadow,” the very real aspect of himself that he tries to smother but will not die. As a result, by allowing him to fester and brood and denying him any room to express himself, Norton is literally assaulted by his shadow, which completely takes control of him. As I said before, Norton’s diametric aspects of his consciousness, which we all possess, manifest themselves as two different people in what’s colloquially known as “split personality disorder.” It’s questionable if this mental illness really exists, but it’s used well here in two interesting characters, one pathetically funny and the other witty, hip, and alluring.

Fincher juxtaposes Norton’s clean apartment as ego with Durdens ramshackle abandoned house as unconscious. Nortons entire apartment is depicted like a commercial, with the names and prices of everything appearing on the screen as they would in a catalog, which is in fact what he spends his time reading. Durdens house, on the other hand, is filthy, empty, falling apart, and Norton speculates that it was abandoned and Durden is squatting there. To make this point explicit, that Durden dwells in Nortons subconscious, there’s a scene in which Norton and Marla are talking in the kitchen, and Durden admonishes Norton for talking about him to Marla. Durden speaks in hushed tones to Norton *from the basement,* actively portraying the Freudian relationship of the ego existing “above” the Id. In fact, this spatial relationship is referred to with the prefix “super” in “superego.” Freud's model is at least partially based on brain anatomy, for the lower brain is whence arise the base instincts and faculties, such as breathing and heartbeat, while our thoughts occur in the frontal cortex, which is physically above the un- or “sub” conscious. Two other regions of the brain that exist physically below the frontal cortex, and control functions associated with the Freudian Id, are the amygdala, which regulates sex, and the hypothalamus, which regulates both sleep and violence.

Marla plays a central role in the manifestation of Tyler Durden and, I will argue, in the eventual resolution of the plot. Marla is the proverbial MacGuffin of the film, the device around which the entire story revolves and from whom or what the characters derive their motivations. This may not be immediately obvious, because most of the screen time goes to Norton and Durden, and they occupy the popular imagination regarding this film. However Marla is in fact the entire reason Durden exists, and the reason Norton gets rid of him. It is also upon her whom my argument against the homosexual interpretation of this film hinges. Before we examine that read, let's conclude with the straightforwardly psychoanalytic interpretation.

Norton says explicitly that Marla “ruined everything.” Exactly how needs to be examined, because when he first meets her he says he “can’t cry if there's another faker present.” This means he will not receive the release from the tension created by suppressing his Id and he will return to suffering from his neurosis. However we must understand that Norton is currently trapped within his neurotic cycle, he just isn’t suffering the physical side effects of insomnia if he continues to cry at the meetings. But he also says, in the same scene, that these meetings “become an addiction,” that he’s obsessively deriving this release from attending the meetings in order to maintain the facade of his consumer identity. This feeling is evoked by his description of Marla, by calling her the “sore” at the roof of your mouth “that would heal if you just stop tonguing it.” We could, perhaps, consider Tyler Durden the sore that wouldn’t heal, Nortons unconscious desires that never went away but were only ignored, until Durden became such a presence that Norton could no longer ignore him. What that sore is, exactly, is sexual attraction for Marla that prevents him from continuing to effectively repress his Id.

Marla “ruins everything,” I contend, by awakening Nortons sexual desire and causing it to rapidly and violently rise to the surface, manifesting as Tyler Durden. Along with this unleashed sexuality comes unleashed violence, two manly instincts that need repression if one is to navigate the sterile business environment of cubicles and “cornflower blue” ties. The Id and the ego must be effectively separated for a man to participate in society, and Freud argues this directly in his book Civilization and its Discontents, in which he claims that a stronger man will not abuse a weaker man for the knowledge, provided by the Superego, that other weaker men who witness this abuse might band together and overpower the stronger man. This is the condition of the subject *in* civilization in its rawest, most simplistic form. We may elaborate on it to say that things like religion or other moral codes create a system of restraint that keep a mans violent or sexual impulses in check, but relevant to Fight Club are the material rewards provided by restraining your impulses to participate in consumer culture.

Norton, for example, makes himself subservient to his boss, going through the motions of small talk and corporate speak in order to fulfill his job duties, in exchange of course for his Ikea apartment. By nortons exasperated tone and the way he anticipates what the boss is going to say, it can certainly be implied that Norton could do a better job than him, but we dont ask right away if he could beat him in a fight. Regardless, we know that is the condition for many men in society, whom Norton is clearly the everyman, and perhaps the superior specimen to his supervisors professionally and physically, but beneath him in the corporate and societal hierarchy. The unfulfilling nature of office and corporate life was in fact a prevalent theme in nineties cinema, probably in reaction to eighties yuppiedom and celebrated materialism, a burgeoning cultural disposition hostile to mainstream, business fashion sensibilities and prescribed capitalistic lifestyles which reached its apogee in Fight Club (see “Office Space, “Falling Down,” “Glenngary Glen Ross,” “Jerry Maguire,” and “American Psycho”). It is the aforementioned societal restraint mechanisms that lead Norton to repress his impulses, do the boring work of society, and allow civilization to function. But we can say for sure later in the film, after Tyler Durden emerges, that Norton could certainly beat his boss in a fight, though he would never be willing to demonstrate it until after the petty reward mechanism of his apartment had been removed. And it was not until his sexual desire for Marla was stirred that his expression of his violent nature was also allowed flourish.

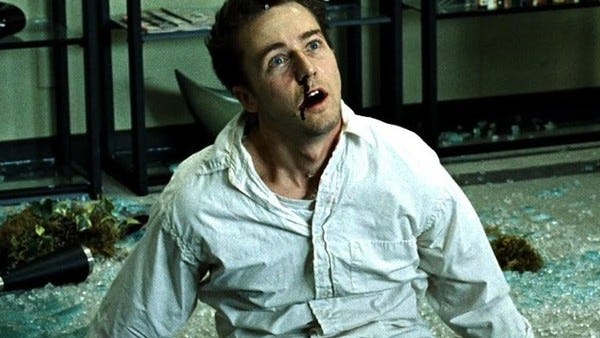

A major theme of this film is the tension between the dichotomous aspects of man, first their separation and then their attempted fusion. Nortons sterile environment loculated all his human needs like the square framing of commodities displayed in a catalog: work in the morning, emotional release and human connection in the evening, sleep, and repeat, with the dirtier aspect of human needs effectively eliminated. Sex and violence eventually erupt into Nortons day to day experience with, as we saw, the introduction of Marla, but the wild, animalistic sex with her occurs off screen and, cinematically, between her and another character. Nowhere is this eruption on better display in the film than the scene in which Norton violently beats himself in front of his boss. While he never attacks the man, his demonstration of willingness to take extreme amounts of punishment to get what he wants shows he is no longer averse to using violence. The message here of course is that Norton is not phased by receiving physical pain, an intimidation tactic he, in the form of Durden, uses to intimidate the mafia Don who tries to break up the basement fight club. His instincts have been fully unleashed now, and not only can he no longer be contained by the parameters of society, but his embellishment of his manly instincts is catching like wildfire. It turns out, men everywhere had been repressing this aspect of themselves, and when they see someone unleashing it, they want to be a part of it.

Nortons violent nature and personal life begin to overlap in ways that begin to make him uncomfortable. His outburst at his job took him out of normal society to focus on Fight Club full time, but eventually Fight Club comes into his home. His living space is overrun by the male members of the club, and Norton becomes aware of their grand scheming. When Bob ends up dead and Norton finds out the club is planning widespread terroristic violence, Norton snaps to action and begins to try stopping Fight Club and put an end to Durdens reign. In other words his Shadow self, and the consequences of his own actions, begin to overtake his life and even threaten to take over society. Rather than incorporating his unconscious urges into his life, he ignores them until they come to the surface and begin to control him. This condition is that of men in society writ large, who beckon the call of Tyler Durden and become his fanatical acolytes.

Norton can’t even go to the police, who also turn out to be members of Fight Club, and he learns that Fight Club cells all over the country are planning terrorist attacks in all major cities. It becomes clear that it’s too late to stop the attacks, but Norton still tries to save Marla by sending her away and diffusing at least one set of bombs, which forces his final showdown with Durden. It must be understood that at this point in the film, the true power of masculine instincts is on display. Not only is Durdens manliness the ultimate fulfillment of female sexual desire, its infectiously attractive to men throughout society, particularly those in the service industry and the police; the very people mentioned above who are the superior specimens to their social betters. As Freud says, if these men don’t repress their violent natures, society cannot develop itself beyond survival of the fittest until the weaker men get a handle on them in some way.

Fight Clubs terror attacks target credit card companies, in an attempt to wipe the slate clean and bring everything back to zero. This can be seen as a reset of society, starting over from ground zero with everyone on a financially level playing field. What this does is break the cycle of societal constraint placed on the stronger men by institutions run by, presumably, weaker men. Once a man is caught in the debt cycle, he is then forced to continue to work to pay it off before he can achieve true autonomy, a cycle inescapable for many people for most of their lives. Once a network of trained fighters is freed from this cycle, suddenly they no longer have to be underground or answer to the old and the weak.

Why does Norton rebel against this? The answer is not quite as obvious as it may seem. It's the death of Bob that begins his rejection of Fight Club, and the subsequent discovery of the terroristic plans that make him try to take it down. Overtly, it appears that he’s finally come face to face with the reality of his violent nature and its potential consequences to get people hurt and killed. Although this is clearly a motivational element, one must ask what happened to his discontent with his previous life, his neurotic cycle, feminization, and fragile ego identity. As we reach the point of plot resolution, we have to ask why Norton wishes to give up the freedom he’s found in this new violent way of life for his old, cowering, unfulfilling life. Is it because “killing is wrong?” Does he have the realization that the mechanism of constraint society places on strong men are the ultimate good, that he’s unleashed something awful that never should have come to pass, and now he’s trying to stop it before he invaluates society's values and allows the strong to take their rightful place? In this scenario, Durden is the villain and must be stopped. Since Norton discovers that *he* is Durden, he shoots himself in the face, thereby eliminating the portion of his brain in which Durden resides, ending the film only as Norton.

This is decidedly *not* Jungian individuation, in which the unconscious is synthesized with consciousness and the ego finds its ultimate expression as a mature Individual. Rather, it’s Nortons desperate attempt to resolve the conflicting aspects when he sees that his unconscious has taken over both his ego and, soon, society as a whole. The message here is that repressed male instincts need to find a way out, lest they break society down in the same way they break down Nortons ego. But Norton was clearly floundering before Durden manifested, believing himself to be an insomniac to the point of death, spending all his free time with people who were literally dying, weeping in the arms of a matronly a man, all in an attempt to make a human connection in his sterile world. And I contend that it was Marla who broke him out of that cycle, and it was for her that he tried to stop Durden and Fight Club.

How does a man, especially an infantilized man, find true, deep human connection in adulthood if not with a woman, specifically a wife and the love of his life? And what do these two do with one another, beyond have sex, if not “make a life together?” A relationship with Marla would allow him to escape his regression with Bob and make himself whole by uniting masculine and feminine, which facilitates the flourishing of his masucline side. However, one cannot make a life with a woman if society is being brought down around him by a terrorist network of liberated men, whose true natures are flourishing with bare knuckle boxing and Spartan barracks living. When Norton realizes he cant stop the bombings, he tries to convince Marla to flee and, when he can’t do that, veritibly forces her onto a bus and tells her to stay out of town for a few days. But she’s there at the end because Durden brings her back, and when the bombs go off, her and Norton hold hands. This final scene also delivers the final message of the film, which is that in order to have a life with Marla, Norton needs to eliminate his carnal, masculine nature. Remember, Durden *is* Norton, so it is really Norton who brings Marla back, because he truly wants to be with her. Once all is said and done, Norton does not reject or continue to push her away, he takes her by the hand at the climactic moment.

The implication here is somewhat two fold, because the bombs do end up going off. So, narratively, Fight Club will ascend. Even though Durden is eliminated, the film at this point has made it clear that Fight Club was set up to function without him, and we can intuit that in this world, the men of Fight Club go on to build their society or, at the very least, reduce the existing one to rubble. But this film works on a highly metaphorical, though somewhat simplistic level. Without understanding metaphor we cannot understand Norton and Durdens relationship as two aspects of Nortons Self. Therefore, the metaphorical imagery of the last scene must be taken into consideration, that of love enduring through the worst catastrophe, two lovers embracing while the world burns, nothing about the outside world mattering to them because they have each other.

What Norton has done is chosen his earlier life over the life with Durden and Fight Club. His life in the beginning of the film was pathetic, played as a complete joke, Norton himself the object of ridicule. Sure, its funny that big fat Bob has big bitch tits, but is that worse than being the man who buries his face in them and cries like a baby? The reason Nortons Id becomes such a problem is that this life was leaving him incomplete, and the final takeaway is that Marla completes him. However, this creates a conflict for the viewer on what to think about Durden, Fight Club, and the other life Norton created for himself. Upon first glance, it would appear that this way of being was “bad” and that Durden was the “villain.” However, we must remember that in order to be with Marla, in order to be with a woman and “have a life” together, Norton has to shoot himself in the head! He has to “kill” an entire, natural aspect of his being. If it was as simple as Norton “overcoming” his urges and integrating him into his waking life, Durden could have just disappeared, Norton could have thought him out of existence.

Instead, Norton has to effectively lobotomize himself in order to remain in society, which is also what happens to Jack Nicholson's character in One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest. In both cases the protagonist cannot do the work of the Superego and mediate the disparate aspects of himself, though of course here Norton chooses this fate, and he’s taking out his lower faculties while McMurphy (Nicholson) has his higher faculties removed. In the book, Norton ends up in a mental institution, again like in Cuckoos Nest, creating different implications for the ending, but the messages of both stories is that men are “trapped” in society in the same way they’re trapped in a psychiatric prison. If their true natures are to be embellished, the institutions of control are brought down around them. But the film unambiguously condemns Nortons earlier life, Fight Club is known as a satire, and we must ask *what* it is satirizing. Clearly, Nortons sterile life, therapy, the cubicle work environment, consumer culture, and capitalist modernity as a whole.

If we consider the entire movie as a celebration of masculinity, the final scene, which I’ve presented here as a standard, sappy love story, is completely turned on its head and shown as a failure. Norton surrendering. He has to give up what made him happy to be with a woman. Perhaps the viewer would say that no, he’s giving it up because he sees the consequences of his actions, because he’s responsible for getting people killed. But that isn’t stopping any of the other members of fight club. They are full steam ahead, they’re completely on board with the final plan of project mayhem: total liberation. It is only when Nortons weaker side wins out, by out-maneuvering Durden, that we reach the synthesis of the ending, the joining of the masucline and feminine.But remember, this is synthesis on Nortons terms. This is not what Marla wanted initially, and at the resolution of the film, she still doesn't know what's going on, about Nortons dual nature. She always wanted to be with Durden, it was Norton that was pushing her away. If it wasn’t for his misgivings, she never would’ve needed to be brought back in the first place. She too, along with all the other men, loved Norton for his aggressive masculinity, not his meekness. When considering Nortons initial infatuation with Durden and his way of life, one may see it as an attempt to regain the wild youth he apparently missed out on, and his maturation at the end as his rejection of that adolescent freedom. But it's too late for that, the film has already shown the life of an insurance company man to be wholly unfulfilling. When the ugly side of true freedom reveals itself, when the ultimate manifestation of male violence becomes undeniable, Norton flees back into the matronly arms of the very society he ran away from. The final message of Fight Club is not that Norton is making the right choice, but that in order to live in this world we find ourselves in, to “settle down” with a woman, our masculine natures have to be murdered. A part of ourself has to die.

"How does a man, especially an infantilized man, find true, deep human connection in adulthood if not with a woman, specifically a wife and the love of his life?"

Arranged marriage.

hey what happened to telegram? did I get banned or did you remove the @?